Hello PTFS friends,

Since I wrote you last, I’ve been traveling. In fact, I wrote most of this dispatch on an Amtrak train en route from Washington, D.C., to New York City. It was a jiggly wiggly typing situation and the wi-fi was spotty but the train was easier than a plane (no near undressing for TSA!). I also like how the train conductors bark orders as we’re boarding. It’s old fashioned. Everything was swell until the train got stuck in Newark, NJ, and I ended up taking the PATH train into lower Manhattan where my friend Dennis picked me up. There is little travel glamour these days but despite the hiccups, things do work out in the end.

As I mentioned in the last newsletter, I went into the Ever-Green Vietnamese book launch with trepidation. Cookbook authors typically hit the big coastal cities but this time around, D.C. extended a warm invitation and I said “Yes!”. I’d not been back to the nation’s capitol in about ten years. It’s become a food town with award-nominated Asian restaurants like Moon Rabbit by Kevin Tien at the swanky Wharf and Thip Khao by Seng Luangrath in gentrifying Columbia Heights. Go for Kevin’s modern takes on Asian dishes like Vietnamese-style bo kho short ribs with carrot pasta (left). Seng’s pun mieng collard leaf wraps with pineapple sauce (right) are intriguing and delicious.

Balancing modern and traditional cooking at those restaurants is also what home cooks are doing nowadays. I sensed that from the conversations I had with people who attended the DC events (a pop-up signing at Bold Fork Books cookbook shop and a ticketed chat and signing at the Smithsonian). They were very well attended (yay!) and I even got to personally thank my long time recipe testers Laura and Hugh. Additionally, they were opportunities to feel people’s anticipation and excitement about Asian food and cooking. Cookbook authors produce “service” writing with the aim of helping people’s lives but we often don’t know how much impact we have because we don’t get to meet many people face to face.

There were touching stories shared at the events. For instance, two sisters reminded me that I’d coached them via Instagram’s direct messages so they could prepare a surprise Vietnamese meal for their mom who had to work late one Christmas. They asked me to sign their copy of Vietnamese Food Any Day (for them) and Ever-Green Vietnamese (for their mom). As I signed their book, I was stunned that they took time to say “Hello”. Such kindness. One non-Asian man said that over years of repetition, he had memorized my bò kho beef stew recipe from Into the Vietnamese Kitchen and looked forward to the mushroom and white bean version in the new book, which he purchased for his vegetarian daughter in law. “I want her to add Vietnamese food to her cooking,” he said.

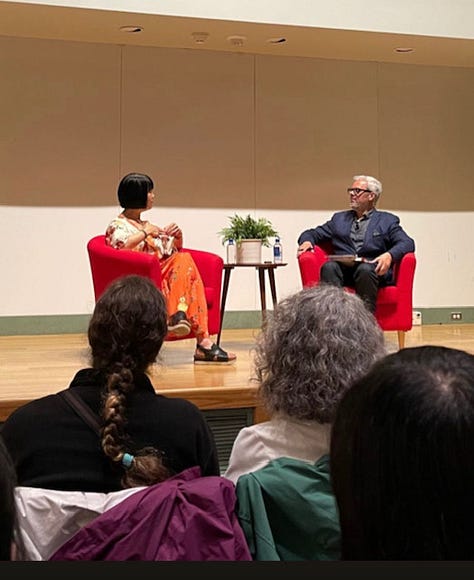

I also met cooks who were simply looking for new vegetable forward, plant-based ideas. “I’m so happy people no longer look at me weird for picking the meat out of food,” one woman said. Gone are the days when eating meatless meals is regarded as freaky. In fact, Washington Post food section editor Joe Yonan interviewed me for the Smithsonian event. He is vegetarian and has written cookbooks, such as Cool Beans. I’m an omnivore who eats a low-meat diet. We both love vegetables, including tofu. We’re all coexisting.

Vietnamese Food Trajectory: Where’s It Going?

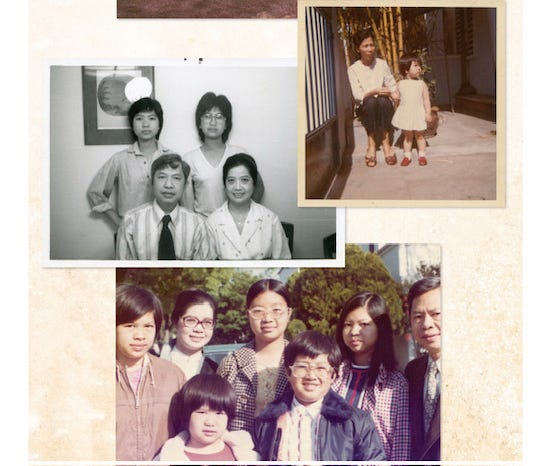

The Smithsonian event in D.C. happened on the forty-eighth anniversary of the Fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975. Washington D.C.played a major role in modern Vietnamese history. A U.S. State Department employee got our family out of Saigon a week before the Fall, and my mom worked for U.S.A.I.D. in Vietnam.

This past Sunday’s event got me thinking about my family leaving Vietnam and how the Vietnamese American community has developed over the decades. I don’t write solely for Vietnamese people because food and cooking belongs to everyone who wants to try.

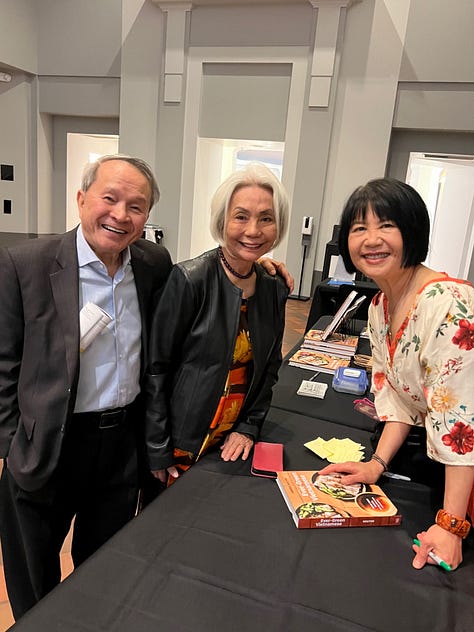

For years, people who came to my events were mostly non-Asian but that’s been changing, especially as Millennials and Gen Z are getting into exploring heritage and cuisines. About half to two-thirds of attendees have been of Asian descent, probably 28 to 55 years old. Surprisingly, a 70-something Viet couple (below, top row, right hand) showed up at the Smithsonian. Dressed smartly in a lovely áo dài and leather jacket, she asked about my position on using Costco rotisserie chicken for banh mi and pho. I pointed her to recipes in the Banh Mi Handbook and Pho Cookbook. Rotisserie chicken has a place in Viet cooking. It’s in line with what inventive cooks would do. Have no shame.

The last question at the Smithsonian was this: Where do you think Vietnamese food is going in this country?

Americans are more fluent now in global cuisines was my response. For example, for years, I titled my recipes for nuoc cham as “Vietnamese Dipping Sauce”. For the new book, I called the recipe “Nuoc Cham Dipping Sauce,” knowing that nuoc cham (“nook chum”) is a term that’s become more familiar to many. (Maybe it’ll be as widespread as salsa one day?)

The morning after the Smithsonian, I thought about Vietnamese steamed rice rolls. Bon Appetit magazine recently unveiled a massive online package of articles and recipe on noodles. They asked me to share my bánh cuốn (“baan coon”) recipe from Into the Vietnamese Kitchen (2006). Bánh cuốn rice rolls are traditionally made from a slightly fermented rice batter that’s cooked on a fine stretch of fabric set over steamy hot water. The iconic treat is tricky to make and mostly left to the professionals.

However, in the 1970s, a nonstick skillet method rose in popularity. Back then, rice flour wasn’t easily found at American supermarkets so people substituted Swans Down cake flour, which had the fine texture and brilliant white color to mimic Southeast Asian rice flour. The cake flour trick actually had circulated in some circles in Saigon prior to April 1975. When Viet refugees got to America, many began using cake flour and nonstick skillets for their bánh cuốn.

My mom swore by that method for decades. When I wrote Into the Vietnamese Kitchen, I thought it odd that rice rolls were made from wheat-based cake flour so I developed my batter to feature actual rice flour, thereby returning bánh cuốn closer to its Vietnamese roots. Now, Mom used my recipe. Check out my skillet bánh cuốn recipe at Bon Appetit.

But wait, there’s more. Seventeen years later, I am presenting a new hack for bánh cuốn that involves over soaking rice paper. The method is gaining traction with cooks in Vietnam — not the diaspora. My mom, 88, deemed the rice paper trick a game changer. She is ready to make the switch, I think.

Handsome and also symbolizing the transpacific flow of culinary information going on today, the 2023 bánh cuốn iteration graces the cover of Ever-Green Vietnamese. The main recipe features a vegan filling of shiitake, cauliflower and carrot. The variation in Notes includes options for shrimp and/or ground meat fillings. When you make the EGV bánh cuốn recipe, if you need an extra assist, there’s a recipe companion video posted on my website with other Ever-Green Vietnamese bonus tips. Here it is for your convenience!

Taken together, the bánh cuốn recipes illustrate the arc of Vietnamese cooking. The skillet method reflects political upheaval and the diaspora. The rice paper method reflects the free-form flow of internet knowledge. You can make the iconic rolls different ways and you’ll still be honoring Viet food.

Share Your EGV Experience

As you cook through the new book, let me know your thoughts. For example, share photos on social media and tag me! I love getting a small look into your kitchen to see how you make my recipe yours. In the span of a week, one person made the baked char siu bao twice. Yowza.

And, please leave a review of Ever-Green Vietnamese on Amazon or wherever you purchased the book. Reviews help others determine the book’s worth and value. Your insights matter a lot.

Events: NYC, SF, and Seattle

Lots is in store for the rest of this month:

NYC, 5/6, 11am-1pm, Union SQ Greenmarket/Kitchen Arts & Letters, taste + signing

NYC, 5/7, Ban Be, unfortunately was cancelled so come to the Greenmarket!

NYC , 5/8 Banh NYC, Green Monday dinner + signing (sold out)

NYC, 5/9, Saigon Social, Street Eats Feast dinner + signing (limited space left)

San Francisco, 5/13, CAAMFest, talk with Soleil Ho + signing

Zoom, 5/18, Early Bird Bonus Cooking Class (sign up!)

Seattle, 5/24, Ba Bar Green, Pan-Asian dinner + signing (limited space left)

The weather in New York City should improve this weekend so maybe I’ll see you? If not, just leave me a comment or send me a Note in Substack’s Notes!

Warmly,

Andrea

Question about rice paper- I shop at a large Viet supermarket and buy all-rice rice paper. I made your baked cha gio tonight. Altho' it was crisp, the texture was kind of leathery, and not light and blistered like it is if fried. I notice that your recommended brands, 3 Ladies and Tufoco Bamboo Tree, have more tapioca flour than rice flour. Does your recipe assume the use of rice paper with a high percentage of tapioca? Would that be lighter?